|

The afro is more than just a hairstyle, it was an incredibly powerful symbol of the civil rights movement. The afro is more than just a hairstyle, it was an incredibly powerful symbol of the civil rights movement. During and after the period of slavery in the United States, most Blacks styled their hair in an attempt to mimic their oppressors. European settlers considered kinky or “nappy” hair unattractive and undesirable. The hair of Africans was often referred to as cottony and woolly. Europeans deemed their straight and fine hair texture as the ideal. Black hair was the antithesis of the Euro-American standard of beauty thus possessing nappy hair was negative and shameful. The Civil Rights Movement sparked a change in the way Blacks viewed their hair and themselves. The movement was a catalyst for Blacks to embrace who they were were naturally including their hair texture. In the African American community, there was a renewed appreciation for the Black aesthetic resulting in the popular phrase “Black is Beautiful”. The afro became a powerful political symbol that reflected the pride one had in their African ancestry. No longer were Blacks attempting to assimilate. Prominent Civil Rights activist, Angela Davis, one of my inspirations, rocked a picked out ‘fro which led many women to follow in her footsteps. A Black person wearing a ‘fro was dubbed as militant and threatening. This notion was promoted by law officials, politicians and the media. Maybe you weren’t able to read inbetween the lines but basically, Black people loving themselves was frigthening to mainstream America. It is important for us to remember our history and the power symbols possess. For me, rocking my hair in it’s afro texture meant I was choosing to love and accept my Black self and I would no longer use abrasive methods in an attempt to alter who I was naturally. I hope it’s more than just a ‘style for you as well. With the deaths of Eric Garner, Travyon Martin and Kendrick Johnson—I believe a new movement for Blacks in America will begin soon. It seems like the natural hair movement will make a perfect pairing once again. From Essence

0 Comments

Widely renowned as one of the greatest jazz vocalists of all time, Billie Holiday had a stunning voice, whose smoky tones and raw emotion still cause a pricking at the back of the eyes and a lump in your throat nearly seventy years on. Holiday complemented her showstopping stage performances with a standout trademark beauty look - white gardenias pinned in her hair. What a sight she must have been, standing in the spotlight with a spray of white blooms tucked behind her ear, glowing brightly against her gleaming black hair. Despite lacking formal training and never learning how to read music, her undeniable musical talent means she is still held as a singing gold standard, and her beauty signature still provides inspiration for countless would-be icons. Flashback While her on-stage look of hair garlanded with gardenias became her trademark, it came about by accident. Rumour has it that Holiday burned her hair with curling tongs one evening, just before she was due to take the stage. One of her fellow performers remembered that a neighbouring venue sold flowers at the cloakroom, so she nipped off and came back brandishing a bunch of the white blooms, which Holiday then pinned in her hair. Holiday liked her emergency hair cover-up so much that from then on, she would be rarely seen on-stage sans gardenia. Her penchant for the flowers did lead to blood being spilt on one occasion, at her sold-out Carnegie Hall show in 1948. According to her autobiography, she was sent a box of gardenias, which she secured to her head without a second thought. Unbeknownst to her, there was a hatpin in amongst the flowers that, having cut the side of her head, made her pass out at the end of her third curtain call. From The Telegraph

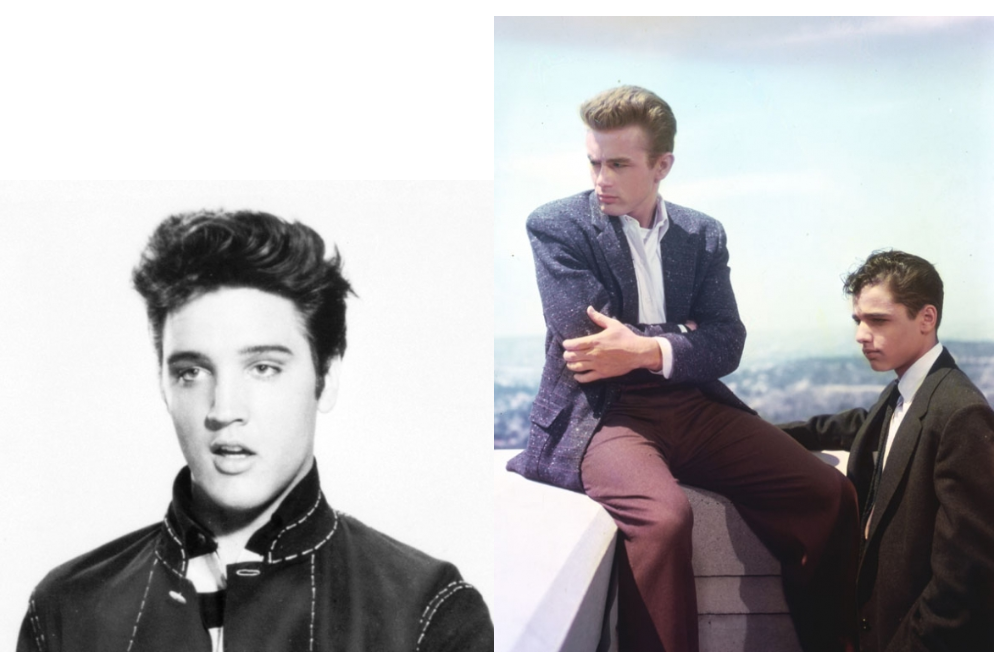

It's clear that hair plays an important role in popular culture. Hair trends help to define each new generation and separate it from the one that came before. The 1950s saw drastic changes in hair styles as teenagers and young adults strove to break free of the previous, more conservative World War II era. Everything from rebelliousness to full-on glamour was embraced by movie stars and singers, and was reflected in new fashion and hair trends seen across the country. Scroll down to see our list of 9 of the most iconic hairstyles of the 1950s! 1. The Poodle Cut Made popular by actresses like Peggy Garner, Faye Emerson and Lucille Ball, the poodle cut was given its name due to the fact that the permed, tight curls closely resembled the curly hair of a poodle. 2. The Bouffant Perhaps one of the most prevalent styles of the 1950s, the bouffant, which would later give way to the amped-up, towering "beehive" style, involved dramatic volume, backcombing and ample use of hairspray. Stars like Connie Francis and Sophia Loren, who brought the "European bouffant" to the United States, were fans of the look. 3. The Pompadour Rebelliousness was celebrated by the younger generation of the 1950s, and nowhere was this so greatly reflected than in the widely-popular pompadour hairstyle. Stars like Elvis Presley, James Dean and Sal Mineo adopted the look - longer hair that was greased up on top and slicked down on the sides, earning wearers of the trend the fitting nickname, "Greasers." 4. The Pixie Though the pixie gained even greater momentum during the 1960s, Audrey Hepburn's closely-cropped hair in the popular film Roman Holiday began a trend of super short hair coupled with soft, wispy bangs that remains popular today. 5. Thick Fringe Short, full fringe began to grow in popularity during the 1950s, especially when paired with long, curly locks made to look natural. Pin-up model Bettie Page popularized the sultry look in her signature dark shade. 6. The Duck Tail Also known as the "DA," this popular 1950s men's hairstyle was named for its resemblance to the rear view of a duck, and is often considered a variation of the pompadour. Though the look was developed in 1940 by Joe Cerello, actor Tony Curtis is widely credited for reviving the style, which involved slicking the hair back, and then parting down the center from the crown to the nape of the neck. The top was then purposefully disarrayed, with long, untidy strands hanging down over the forehead. 7. Short & Curly Many actresses and female singers of the 1950s, including Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe and Eartha Kitt, favored this shorter, slightly less voluminous version of the classic bouffant. Perfectly curled and coiffed hair was the signature of this look, though great care was taken to make hair appear to be naturally curly. 8. Ponytails Though the look was often seen on young girls and teenagers and commonly paired with poodle skirts, the ponytail began to become popular for women of all ages during the 1950s, as evidenced by singer Billie Holiday. 9. Sideburns Another men's hair trend that went hand in hand with the pompadour and a sense of rebelliousness was the sideburn. The look was seen on actor Marlon Brando in the film The Wild One, as well as on actor James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, and soon made its way into mainstream culture. From BeautyLaunchPad

10/17/2019 0 Comments Hair To Dye For: Radical RedheadsFamous Red, Orange, and Auburn Haired Ladies Flaming hot since 1558! I’m a sorta-redhead. My hair can’t decide whether it wants to be mousy, dishwater blonde or a snappy strawberry (which makes picking out outfits a drag since some colors look good with redheads, but not with blondes and vice versa). My hair’s indecision began when I was just a baby; I have a natural pink mohawk in most of my baby photos thanks to my light strawberry blonde curls piling on top of my ivory skin. My hair turned blonde and straight when I was two, then switched back to curly auburn when I was 16. By junior prom, I was sick of my hair flip-flopping from red-to-blonde-to-brown-to-all-three. L’Oreal Excellence Creme in it’s cute, pink box promised to even out my hair color in just 30 minutes and a shower. Who was I to refuse? Dousing my unruly hair with dye disguised my hair’s spotty nature, and it’s pretty historically accurate at that! Natural redheads are mutants (with recessive variant genes). Our superpowers are sticking out in a crowd and looking awesome. Many have scorned our powers by flogging us with insults (“Gingers have no souls!”) while others have venerated our hair’s glory with paintings, festivals, films, and flattery. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, redheads are the most flattered of all hair colors: Sixty percent of women who dye their hair do so at home. Of them, twenty six percent choose to go blonde, twenty seven percent go brunette, and over thirty percent choose to become redheads! Feel the power! The see-saw between scorn and veneration has been going on since redheads were first documented in Greek writing. Boudica, the warrior queen, is said to have had long red hair that–in addition to her stature–was a terrifying, powerful sight on the battlefield. The idea that redheads have fiery tempers stems not only from the flame coloring, but also from the politically powerful redheaded women like Boudica who were just as powerful and intelligent as men (if not more). This was naturally unnerving to a society in which women were expected to be subservient. Throughout history– even through the 1950s– redheaded ladies have been breaking rules and changing social norms! Queen Elizabeth I Perhaps the most famous redhead in history is England’s Queen Elizabeth I. Born to Hanry VIII’s most notorious wife, Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth inherited her father’s golden-red hair. When she took the throne in 1558 at the age of 25, she brought wit and unprecedented political prowess with her. She refused to marry and actively participated in the jurisdiction of her country. Though she was affectionately called the “virgin Queen,” she is reported to have taken many lovers and favorites throughout her long reign. Beloved by her subjects and lauded for her role in England’s victory over the Spanish Armada, Queen Lizzie changed red hair from a fashion faux pas (blonde was the previous preferred color) into England’s must-have shade. Elizabeth’s striking red hair set off the creamy whiteness of her skin. Light skin was considered to be the most important aspect of beauty and since the recessive gene that creates red hair also causes paler skin and lighter brows, natural redheads in Elizabethan England became suddenly fashionable. Creamy skin and ruby-tinged hair also meshed well with the rich jewel tones and heavy golden ornamentation that prevailed in courtly fashion. Ladies who weren’t in the lucky 4% of the population with the variant gene, there were all sorts of hair treatments: For coloring the hair so that it is golden. Take the exterior shell of a walnut and the bark of the tree itself, and cook them in water, and with this water mix alum and oak apples, and with these mixed things you will smear the head (having first washed it) placing upon the hair leaves and tying them with strings for two days; you will be able to color [the hair]. And comb the head so that whatever adheres to the hair as excess comes off. Then place a coloring which is made from oriental crocus, dragon’s blood, and henna (whose larger part has been mixed with a decoction of brazilwood ) and thus let the woman remain for three days, and on the fourth day let her be washed with hot water, and never will [this coloring ] be removed easily. I’ve highlighted the word henna because this particular plant was the primary source of red hair colorant since the age of the Pharaohs! Henna is mostly famous as a skin pigment, but this semi-arid shrub also works as a semi-permanent hair dye and was the most popular way to get red hair until synthetic dyes were invented in the late 1800s. Queen Elizabeth herself dyed her hair as she aged and her hair became white. The auburn-red of her earlier portraits fades into a light pinkish-orange since henna is a naturally orange dye that only reddens the base color. If the base color is a brown, it tints it red. If the hair is blonde, henna creates a golden strawberry. By the end of her reign, Queen Elizabeth’s hair was fine and white, so the true color of the henna is revealed in her portraits. The Pre-Raphealites Red hair gained popularity again in the mid-1800s, culminating with the Pre-Raphealites and their beautiful models like Fanny Cornforth, Alexa Wilding, and Elizabeth Siddal: ladies with deep burgundy and ginger-flamed hair. The Pre-Raphealite Brotherhood, a group of artists, began in 1848 and lasted for an all-to-brief decade. Their influence on artistic style and fashion was much longer lived. The mauves, greens, and blues of dreamy pre-raphealite paintings were perfectly suited to complement cascading red hair. Paired with swaths of roses and loosely draped gowns, pre-raphealite paintings recreated classical Greek, Medieval, and folk fashions with a heavy dose of dreamy fantasy quite unlike the rigid world of corsets and hoopskirts in the 1850s and 1860s. There was plenty of controversy surrounding these sensual models, especially considering that many were mistresses of the painters themselves! These ladies appear unfettered by any social, sexual, or fashion restraints in their pictures: clinging silks drenched in rain hug every curve, a corsetless waist is girdled softly with gold, and hair flies around their shoulders freely. Though the fashions might be too much for the everyday Victorian lady, glowing crimson locks were well within the average woman’s reach. The red-haired beauties filling the canvases inspired women to once again run to their nearest druggist for the reddening power of henna dye. Lucille Ball No list of spunky, game-changing redheads would be complete with Ms. Lucy! The saucy sit-com queen is famous for her brilliant red mound of spunky curls. From 1951 to 1960, Lucille Ball entertained the world on her TV shows I Love Lucy and The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour. Though these are her most famous accomplishments, Lucille’s resume includes much more, including modeling, a brief stint as a Broadway chorus girl, and acting work in films alongside the Three Stooges, Ginger Rogers, and Katherine Hepburn. She’s known for being outspoken and participated in a few small tiffs with social norms, most famously her marriage and divorce to Desi Arnaz. Ball met and eloped with the Cuban bandleader in 1940. Lucy was 6 years older than Desi, sparking a little social friction since some people thought an older woman marrying a younger man was improper. During her first pregnancy, Lucille continued to film I Love Lucy even though she was showing, but the broadcasting company forbade any mention of Lucille’s “condition” on-air. Lucille’s and Desi’s first child, Lucie Désirée Arnaz, was born when Lucille was almost 40 years old! Lucille’s second pregnancy, however, is the one she is most famous for. TV in the 1950s was heavily censored and everything that went on air had to be approved by a committee. This time around, Lucille’s real-life pregnancy was worked into I Love Lucy’s plot. In a magnificent segment, she appears on camera, glowing, to surprise Ricky with the news. It was a huge moment in television history. Even though much of her film and TV work was done in black and white, Lucille Ball’s hair was a key part to her personality and characters. In fact, we associate the color red with her so much, it’s hard to recognize her with any other haircolor: Here’s a bit of a surprise: Lucille Ball was not a redhead. Lucille Ball was actually a natural brunette/dark blonde, but she dyed her hair using that fabulous plant dye, henna. As her fame grew, so did the demand for red hair dyes, driving the sale of natural henna color through the roof. The queen of mid-century comedy continued to dye her hair throughout her life, maintaining the titian tint that came to define her.

Today, most hair dyes are synthetic and can be done at any hair salon, or at home with a box kit. The coloring agents come in liquids, foams, brushes, and sprays in every color under the sun! With all these magic concoctions so readily available and inexpensive, it’s hard to imagine that such a seemingly innocuous thing like dying your hair for prom or using a color rinse shampoo before a date could have such a huge impact on fashion and society. What if Elizabeth had been raven-haired? What if Pre-Raphealite painters preferred blondes? What if Lucille had never dyed her hair that brilliant orange-red? Knowing that so much of who you are as a person can be linked to something as simple as hair color makes me wonder: What’s my “true” color? While Americans today expect to see soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coast Guardsmen with closely clipped hair, many don’t realize that hair standards in the armed forces have changed radically since the American Revolution. A lack of barbers in the American colonies in the 18th century meant that soldiers in the Continental Army usually had rather long hair, wrote Randy Steffen in the authoritative The Horse Soldier 1776-1943. Nonetheless, general orders published by commanders required male soldiers “to wear their hair short or plaited (braided) up.” But a Revolutionary-era soldier also had the option to wear his long hair “powdered and dried.” Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who led Union forces to victory in the Civil War, was one of many soldiers of both sides sporting facial hair during the conflict. National Archives photo Although hairstyle rules were relaxed when soldiers were on campaign, Continental Army personnel who did powder and tie their hair did so with a mixture of flour and tallow, a hard animal fat. This powdered hair was usually tied in a pigtail or “queue.” In the late 1700s and early 1800s, cavalrymen preferred a “clubbed” hairstyle in which they gathered their hair at the back of the neck and tied it in a firm bundle, then folded it to the side before finally tying it again in a club (basically a folded pigtail). Mounted troopers liked the club because it was “likely to stay in place during the excitement and violent action of a mounted fight.” Beards were forbidden in the Army of the early Republic and soldiers were required to shave a minimum of three days a week, at least while in garrison. A major change in military hair rules occurred in 1801, when Maj. Gen. James Wilkinson, commanding general of the Army, abolished the queue. Some historians believe he took this action because the pigtail was an aristocratic affectation that had no place in an egalitarian republic, but whatever the reason, Wilkinson’s decision caused soldiers to “howl in protest, until their resentment swelled almost to mutiny,” according to a February 1973 article published in American History Illustrated. It seems that soldiers believed that the short hair requirement was nothing short of self-mutilation. In July 1805, the Army court-martialed Lt. Col. Thomas Butler, Jr., a 30-year Army veteran, who refused to cut his hair. A panel of officers found him “guilty of mutinous conduct in appearing publicly in command of troops with his hair queued.” The panel sentenced Butler to be suspended from command, without pay, for 12 months. This was a severe sentence, given Butler’s seniority and three decades of service. While Gen. Wilkinson ultimately approved the sentence, it was never carried out because (unbeknownst to Wilkinson) Butler had died a few days earlier (probably of yellow fever) with his queue still intact. Lt. Cmdr. Stepen B. Luce, a contemporary of Grant’s, serving in the U.S. Navy, went for a more flamboyant look. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photo When it came to facial hair above the lip, the Army took a very different approach, at least in the years before the Civil War. From 1841 to 1857, regulations provided that “mustaches” or “moustaches” would not be worn by any soldiers except for those in cavalry regiments, “on any pretense whatsoever.” By the Civil War, hairstyle standards had changed markedly, as senior officers in both the Army and the Navy wore beards and mustaches as a matter of course. While a beard could be worn “at the pleasure of the individual,” both services preferred that it be kept short and neatly trimmed. This preference, however, was very much in the eye of the beardholder. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had a somewhat neatly trimmed beard while Adm. Stephen B. Luce had a much more wild look. World War I was the first conflict where shaving was required. There were two reasons: to get a proper fit and seal on the gas mask and personal hygiene. Beards were outlawed, and the maximum permitted hair length was one inch. During World War II, the Army required soldiers to “keep your hair cut short and your fingernails clean,” and most men in both the Army and the Navy wore a medium-short tapered cut. But, while beards were officially outlawed, soldiers and Marines in sustained combat operations sometimes grew beards – if for no other reason than it was too hard to shave under fire. Pfc. Brian J. Magee receives a haircut from a South Korean barber during the Korean War, ca. Aug. 1950. Other Marines in background wait their turn. In combat conditions hair lengths were more loosely enforced. U.S. Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections photo In the last half of the 20th century, hairstyles in the armed forces followed civilian trends, especially in the Army, Navy and Air Force. In the late 1960s, long hair was popular, and soldiers who refused to get a haircut received non-judicial punishment under Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The Navy and Coast Guard, however, simply gave in to relatively long hair and beards: witness the announcement by Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr. – in “Z-gram No. 57” published in 1970 – that beards could be worn by active duty sailors. Zumwalt believed that the Navy must “learn to adapt to changing fashions” and this meant that sailors should have the freedom to wear the long sideburns, neatly trimmed beards and mustaches favored by civilians. Not until 1985 did the Navy once again prohibit beards on sailors, and the Coast Guard, which had followed Zumwalt’s permissive decision on beards, also abolished them a year later.

In the 1980s, the mustache was especially popular in the services. Although still permitted, it has almost disappeared today. Today, short hair is the norm for men in all the services, and women too favor shorter hairstyles. Regulations and instructions on female grooming standards reflect this “shorter is better” style. In the Air Force, for example, a female airman’s hair must be “clean, well-groomed and neat” and hair length cannot extend beyond the bottom edge of the uniform shirt collar; women who have longer hair must wear it “up.” *The standard for woman's hair changed in 2018. Given the long and short history of hair, the future is certain to bring yet more changes in the armed forces. This bit of history was found here. Click here for some photos from Wartime Barbering. Hair doesn't stop growing just because there's a war on, after all. |

Hair by BrianMy name is Brian and I help people confidently take on the world. CategoriesAll Advice Announcement Awards Balayage Barbering Beach Waves Beauty News Book Now Brazilian Treatment Clients Cool Facts COVID 19 Health COVID 19 Update Curlies EGift Card Films Follically Challenged Gossip Grooming Hair Care Haircolor Haircut Hair Facts Hair History Hair Loss Hair Styling Hair Tips Hair Tools Health Health And Safety Healthy Hair Highlights Holidays Humor Mens Hair Men's Long Hair Newsletter Ombre Policies Procedures Press Release Previous Blog Privacy Policy Product Knowledge Product Reviews Promotions Read Your Labels Recommendations Reviews Scalp Health Science Services Smoothing Treatments Social Media Summer Hair Tips Textured Hair Thinning Hair Travel Tips Trending Wellness Womens Hair Archives

June 2025

|

|

Hey...

Your Mom Called! Book today! |

Sunday: 11am-5pm

Monday: 11am-6pm Tuesday: 10am - 6pm Wednesday: 10am - 6pm Thursday: By Appointment Friday: By Appointment Saturday: By Appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed